Painting Pleasure

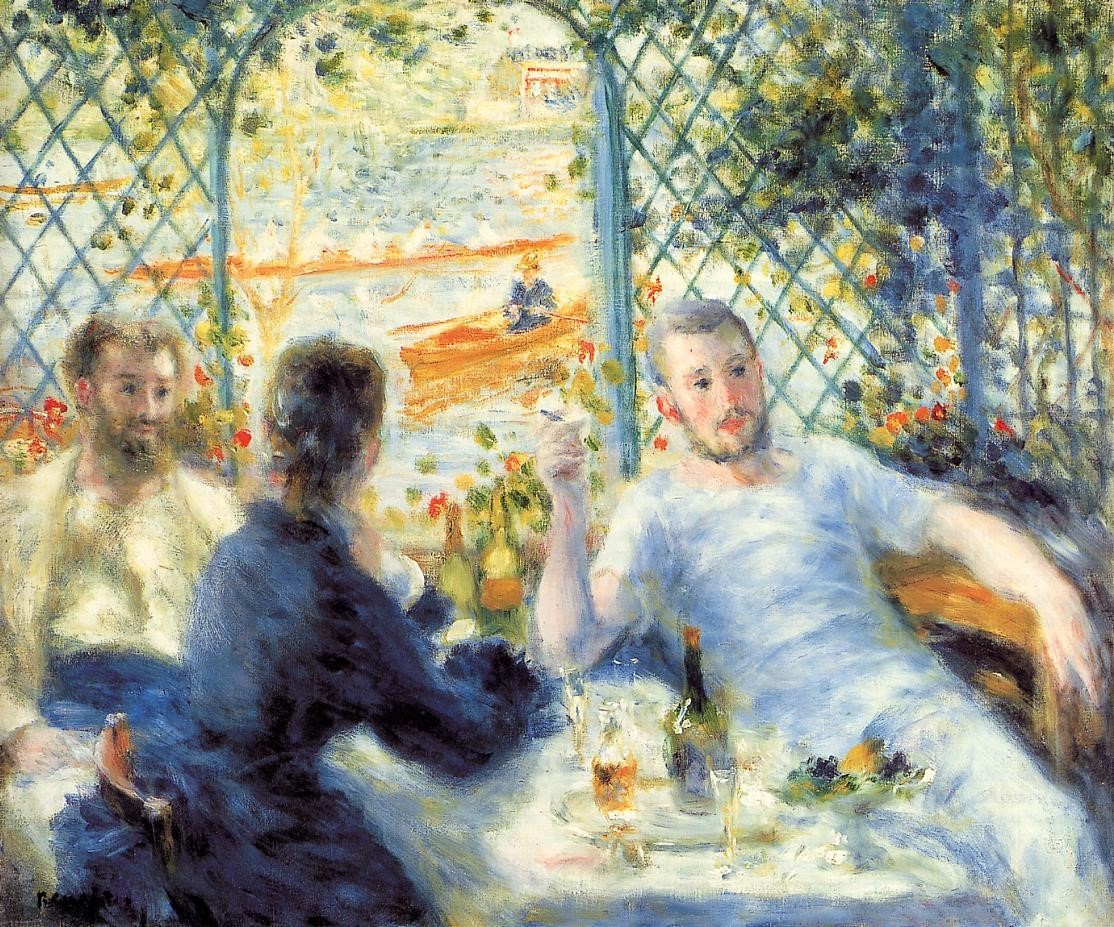

Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party (Le Déjeuner des Canotiers) affords one the rare pleasure of looking in on the cheerful charm of a group of Parisians enjoying a moment of leisure along the Seine river in the late 1800’s. Such moments of pleasure and conviviality are often accompanied by wine, as is this case here. In the center of the painting we can see bottles and glasses of wine on the table, around which unfolds conversations, flirtations, sentiments and intrigues. However, as is often case, while wine may be the center piece of such occasions, it is not the focal point but rather the axis on which the wheel turns.

One of Renoir’s largest paintings, Luncheon of the Boating Party simultaneously combines the styles of portraiture, still-life and en plein air landscape painting while embracing the changing face of French society in the late 19th century. In a dazzling display of flickering light, vibrant colours, and transient gestures, Renoir’s masterpiece celebrates the beauty and joy of the fleeting moment in all its vitality, spontaneity, and freshness. A beauty and a joy which has received overwhelming praise since its debut at the 7th Impressionist Exhibition in 1882.

“It is fresh and free without being too bawdy”

–Paul de Charry, Le Pays, March 10, 1882

“…one of the best things [Renoir] has painted… There are bits of drawing that are completely remarkable, drawing-true drawing- that is a result of the juxtaposition of hues and not of line.”

–Armand Silvestre, La Vie Moderne, March 11, 1882

The painting was bought by the artist’s dealer and patron, Paul Durand-Ruel, and subsequently sold by his son to Duncan Phillips, an American industrialist who spent over a decade looking for it. It currently resides in the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. where it is still celebrated today.

“[it] remains the best known and most popular work of art…. just as Duncan Phillips imagined it would be when he bought it in 1923”

–Phillips Collection website

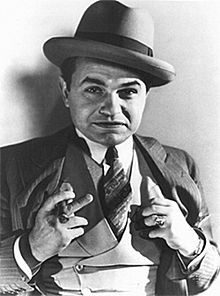

It even captured the heart of the actor Edward G. Robinson, notorious for his gangster roles in the prohibition era, who famously said,

“For over thirty years I made periodic visits to Renoir’s ‘Luncheon of the Boating Party’ in a Washington museum and stood before that magnificent masterpiece hour after hour, day after day, plotting ways to steal it.”

The scene takes place on the balcony of Maison Fournaise in Chatou, France, a restaurant and hotel which offered a boat rental service and was a popular destination for Parisians from many walks of life. In fact, the restaurant clientele was a diverse mix of businessmen, society women, actresses, artists, poets, politicians, and seamstresses, all looking to escape the bustle of the city and relax along the river bank, presumably after a pleasant afternoon boating. Renoir himself was a frequent customer between the years of 1868-1884, claiming…

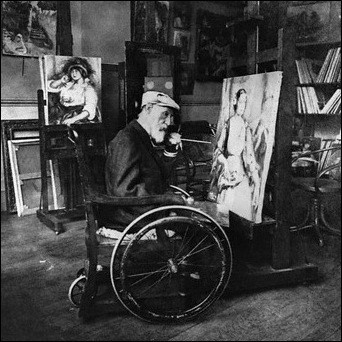

“You could find me any time at Fournaise. There I was fortunate enough to find as many splendid creatures as I could possibly desire to paint.”

Having been popular among other impressionists as well, such as Edgar Degas and Gustave Caillebotte, the Maison Fournaise earned the widely used nickname, “Isle des Impressionists”.

The Figures

What is striking about the composition is how the figures work together to embody a sense of liberalism and playfulness as one’s eyes are guided around the painting. This liberalism was brought on by the ideas of progress, change, and freedom inspired by the industrial revolution and was reflected in French society through a softening of boundaries between classes which allowed for a more relaxed and open atmosphere in social settings and public places.

We can see evidence of this social transformation in the painting through the body language and attire of the figures. For example, there are two men socialising in nothing other than their undershirts and boating caps. One of them is even sat backwards in his chair leaning away from the table, thus in a way shedding the formality and restraint of previous social etiquette. The figures themselves, who were all friends of Renoir, further exemplify a mixing of classes and a freedom of social expression as their personal dramas draw us into the painting, enticing our curiosity of what might be unfolding in that very moment.

In the top left corner we can see a broad-shouldered, bearded man in an undershirt and straw boating cap leaning back against the railing. He is Alphonse Fournaise, Jr., the son of the proprietor responsible for the boat rentals. His gaze directs our eyes to a group in the upper right corner.

There we can see two of Renoir’s intimate friends, the bureaucrat Eugene Pierre Lestringez and the artist Paul Lhote, flirting with the actress Jeanne Samay. However the woman seems embarrassed, perhaps even scandalised, and turns her face away.

Her diverted eyes lead us the young man and woman sitting at a nearby table. The young man is intrigued by the woman who nonetheless appears disinterested and detached as she stares blankly out of the canvas.

This woman, actress Ellen Andrée, was referenced prominently in the film Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain in comparison to the protagonist, a girl who preferred to live in a marvellous world of her own rather than engage in relationships with the people around her.

As she appears disengaged from the scene, one momentarily pauses before drifting to the two men behind her, a wealthy art collector and editor of Gazzelle des Beaux Arts named Charles Ephrussi in deep conversation with Jules Laforue, his personal secretary as well as a poet and art critic.

To their left we see Louise-Alphonsine Fournaise, the daughter of the proprietor, leaning against the railing and seemingly lost in thought. She is looking beyond the man in front of her with his back towards us, a man named Baron Raoul Barbier, former mayor of colonial Saigon and notorious Buon Vivante. He is perhaps trying to catch her attention but to no avail. The charming smile and dreamy eyes of the girl tell us that she is likely thinking about the young man with the moustache standing across the room, as a trail of unrequited admiration continues.

This young man, an Italian journalist named Adrien Maggiolo, looks not at the proprietor’s daughter but at the woman in front of him, actress Angèle Legault, who looks not at him but at the man in front of her, the impressionist artist Gustave Caillebotte. But alas the artist does not return her gaze as he is watching the woman in front of him playing with her dog. This woman is Aline Charigot, a seamstress who later became Renoir’s wife.

And so between gazes across the room, flirtations, even scandals, unrequited admiration, deep conversations, dreamy stares, aloofness and play, we experience the voyeuristic pleasure of exploring the intricacy of the scene as our eyes dance around the canvas.

Balance and Design

Beyond the personal dramas of these figures, their positions and gestures act to create a dynamic sense of dimension in the composition. The crowdedness of overlapping bodies enhances the intimacy of the scene while the striped awning closes in the space giving an internal quality despite the outdoor setting. Renoir also cleverly achieves balance between the two figures in the left foreground and the twelve on the right by slanting the floorboards, making the background of the balcony just as visible as the foreground. The empty space beyond the awning is filled with the lush landscape along the Seine and boats sailing along the river in the distance giving the composition some relief in its scope and breadth.

A sense of space and dimension is also created by the lines in the painting which form a pyramid structure between the diagonal line of the railing on the left and the diagonal of the woman’s arm on the right. This space comes alive with the tension of counterweight and movement as the two opposing figures in white undershirts lean out of the composition while the other figures lean in and around each other.

We can see the wind in the flapping of the awning edges, we can almost hear the voices chattering, the chairs shifting, and the glasses clinking. All of these qualities render the painting full of life and one almost has the illusion of being part of this fleeting moment captured on canvas.

Light, Colour and Texture

In pure impressionist style, this painting is characterised by vivid colours, open brushstrokes and an emphasis on conveying the momentary effects of light. The colours themselves are rich and full of contrast where deep blues and lush greens are set against splashes of red and orange, all in turn reflected by patches of white. There is a gentle warmness in the golden tones of sunlight streaming into the balcony, the straw coloured boaters hats, and the reddening of the women’s fair skin and the men’s bare arms, giving one very much the impression of a warm afternoon.

There is also a sense of movement and vibration in the loosely applied brushwork, at times thick, broken, or delicate and wispy, which shifts from a more conventional use of line and contour to the freshness of fluidity and spontaneity. And it is exactly this shift in painting introduced by the impressionists which offers a new way of seeing and appreciating art. It is the bold attempt of the artist to recreate the visual sensation of the eye absorbing and embracing the immediacy of movement and light and the candid beauty of what’s in front of it.

However it must be said that while the painting seems to capture the essence of the moment, it was somewhat longer in the making. As with many impressionist artists, Renoir did not do any preparatory drawings but rather developed the composition as he went along. Contrary to what it may seem, this process took several months with a transition from painting the landscape en plein air to studio work with the models. The Phillip Collection states,

“Renoir seems to have composed this complicated scene without advanced studies or underwriting. He spent months making numerous changes to the canvas, painting the individual figures when his models were available and adding the striped awning along the top edge. Nonetheless, Renoir retained the freshness of his vision, even as he revised, rearranged, and crafted an exquisite work of art.”

–Phillips Collection website

It is perhaps this very flexibility and openness to change within the artist’s vision that brings the painting to life with so much veracity depicted in the pleasure of passing moments.

Drinking Design

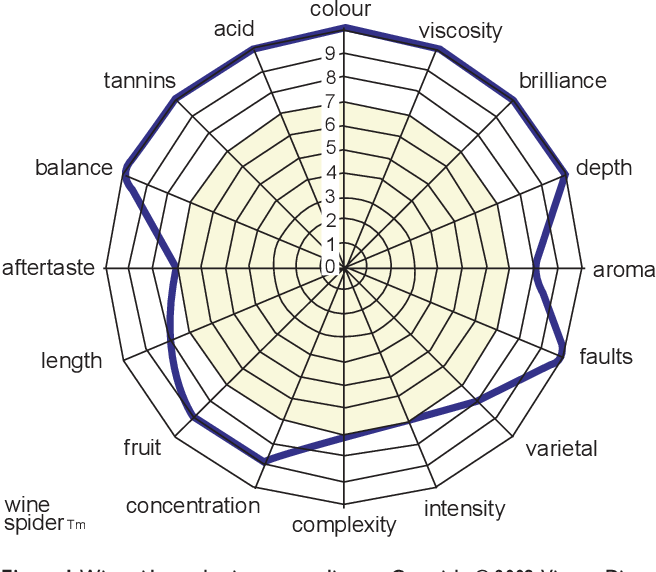

In much a similar way, the experience of drinking wine has an instantaneous effect on our senses, which is nonetheless a product of design. What the painter does visually in way of structure, texture, balance and harmony, the winemaker strives to achieve through olfactory, gustatory, and tactile sensations. Winemakers carefully craft their wine in such a way that we might experience the pleasure of these qualities, giving an aesthetic value to wine.

Structure and Texture

The structure of a wine is perceived in the sensations of sweetness, acidity, astringency and bitterness while the texture is perceived in the sensations of the weight it has in one’s mouth. This may be expressed as delicate, light and fleeting or conversely rich, complex and full bodied with a long aromatic persistence, depending on the type of wine and the style that the winemaker aims to achieve. Interestingly enough, adjectives for the “body” of wine are often related to the human figure: thin, weak, full-bodied, robust or heavy.

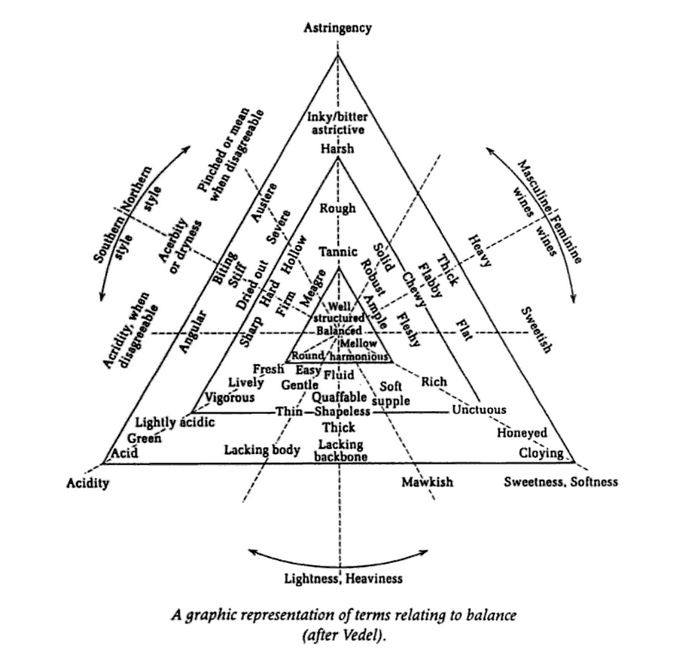

Balance

Balance is the result of the contrast between soft and hard sensations, softness being related to the quantity of sugar, alcohol, and poly-hydric alcohols and hardness to the quantity of acidity, tannins and minerals. Young wines, particularly white, and sparkling wines are often characterised by liveliness due to their predominance of “hard” sensations while aged wines and sweet wines are often characterised by roundness due to the predominance of “soft” sensations. Along the pendulum of this balance swings the qualities of aggressiveness, vigour, vividness, delicacy or meagreness. It is also worth noting that balance is related to the evolution of the wine as it changes through time.

Harmony

Harmony, alas, is the synthesised summary of all the sensations experienced in drinking wine: its appearance, aromas and flavours. If all of these elements are coherent between them and elegant in proportion, the wine creates harmony, experienced in the pleasure of drinking something that is pleasant and delightful for our senses.

And so if the aesthetic pleasure of a painting can find an affinity in the aesthetic pleasure of drinking wine, than it seems apt one should consider the winemaker as a sort of painter for the palate.

Sources:

http://www.phillipscollection.org

http://www.visual-arts-cork.com