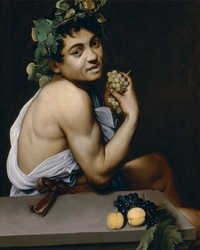

Caravaggio’s Young Sick Bacchus, known also as Bacchino Malato, is an alluring portrayal of illness and vice. Darkened by suffering, it seems nonetheless also illuminated by lust, gluttony and pride. The painting’s own history is interwoven in wrath, envy and greed. In fact, of the seven deadly sins perhaps only sloth can not be said to belong to such a vivid, if not tainted, representation of Bacchus: god of wine, debauchery and abandon.

Signs of illness…

One of the most striking features of the painting is the pallid, jaundiced toned skin of young Bacchus, which gives the figure a decidedly sickly appearance. Many critics, notably Roberto Longhi, believe that it is actually a self-portrait that the artist painted with the use of a mirror during his convalescence in l’Ospedale della Consolazione in Rome, referencing his own physical state. While some sustain that the he was recovering from malaria, others point to a liver related illness to explain the jaundice, but the most probable and widely accepted account is that he was recovering from a wound to the leg caused by a horse kick.

Whatever the cause of Caravaggio’s illness was, the depicted figure is convincingly unwell. Beyond the pallor of his skin, one can see his lips are tinted blue as if lacking vigour and nourishment. Despite his outward turned gaze, his body is contracted inwardly perhaps contorted by pain. Even his eyes seem to express weakness and suffering.

Contrasting symbolism…

Yet, characteristic of Caravaggio’s symbolism is it’s very allusiveness.

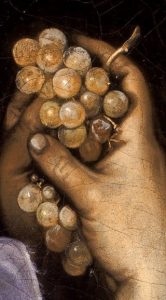

While this is clearly not the plump and jovial, classical depiction of Bacchus, he is still youthful, garlanded in ivy and holding a bunch of grapes as if holding onto his frivolous identity and the pleasures of life while at the same time losing grip on them. Stark contrasts are a recurrent theme in Caravaggio’s works and is exemplified in this painting on many layers. Bacchus is fully illuminated in contrast with a dark background. His body displays a certain boyish physicallity which is however deformed by illness. He is partly clothed yet revealing a nude arm and shoulder. His own physical decay is contrasted by the vibrant, plump fruit laid next to him on the table. The viewer is reminded of the closeness of death yet perhaps hopes that this young, docile Bacchus may still recover from his aliments and return to the joys of life.

The joys of life, in the case of Bacchus, are however laden in vice and excess and it is certainly an interesting choice to potray such an icon, a divine figure nevertheless, in a state of illness, a condition of human frailty.

Is Caravaggio simply refiguring himself as a divine figure in search of some sort of personal consolation? Or perhaps, in more broad terms, the painting reveals an inherent beauty seen from the ugly reality of illness, decay, and imperfection.

Lust

Bacchus was originally a Greek God known as Dionysis, later adopted by the Romans. In Greek mythology, legend has it that Dionysis was the son of Zeus and a mortal woman, Semele. Having had enough of Zeus’s infidelities, his wife Hera sought revenge by convincing Semele to ask Zeus to reveal himself in his divine glory. When Zeus did this, his luminosity was so great as to burn Semele alive. Zeus however rescued the baby and brought him to Mount Nysis, from which this God, born out of lust, took his name.

Lust is a vice in as much as it is an excess of desire leading to immoral behaviour. Normally associated with sexual desire, it is considered the least evil of the deadly sins as it is directed towards love and communion. Although Young, Sick Bacchus is not explicitly sexual, he does have sensual elements such as the draping clothes sliding off his partly exposed torso, the knot of his robe placed on the table as if ready to be unravelled, the supple, parted lips, and the anticipation of physical pleasure in the sweetness of the grapes moving towards his mouth.

Is it Bacchus’s own lust being potrayed, which may have indeed led to his suffering; a lust for physical pleasures unbridled and reckless for which he has become a symbol? Or could it be an appeal by Caravaggio to love this vulnerable Bacchus despite his illness?

Gluttony

If lust is an intense desire, the object of that desire being a physical pleasure related to food through wine indicates also gluttony, and an excessive indulgence in wine is one of Bacchus’s defining traits. The Catholic encyclopaedia states, “It is incontrovertible that to eat or drink for the mere pleasure of the experience, and for that exclusively, is likewise to commit the sin of gluttony”. Thus, food and drink in themselves are not considered vices, but rather the pleasure derived from them which leads to impulsiveness, an abandonment of proper judgement, and a injury to ones health.

As to Bacchus’s illness, the article “The Diagnosis of art: Caravaggio’s jaundiced Bacchus” puts forward that jaundice in late 16th century Rome was often an indication of liver failure and cirrhosis due to chronic alcoholism, or otherwise acute infective hepatitis. The text points out that while Caravaggio himself was not suffering from liver failure, we may assume that he had seen those that were. Moreover, had Bacchus been mortal, his health would have eventually suffered likewise. Yet Caravaggio does not seem to be reprimanding Bacchus’s behaviour, he is so young after all. Instead, he seems to be pleaing for our sympathy.

Furthermore, there is almost a veneration of the visceral pleasures linked to lust and gluttony in the sense that they persist in their appeal and charm not only to young Bacchus, but also to the viewer, drawing one in by seducing one’s senses.

Wrath

Caravaggio painted Young Sick Bacchus while he was under the study of Giuseppe Cesari, known also as Il Cavalier d’Arpino. D’Arpino was a very successful artist at the time, described as a man of ambition and testy temperament, and there is allegedly one incident when his anger and passion for vengeance got the best of him.

In 1607 he was accused of violently disfiguring the artist Cristoforo Roncalli because Roncalli was trying to rob a potential client from him. D’Arpino was arrested and his private collection of paintings, this one among them, were sequestered. He was subsequently proven innocent, however officials of Pope Paolo V found him in possession of pistols and he was therefore forced to donate his paintings in order to obtain his release. The vice of wrath is defined as an excess of anger which leads to a desire for vengeance and harm to others beyond the confines of the law and morality. In the case of d’Arpino, his apparent desire to take the law into his own hands led to the loss of his prized private art collection.

Greed

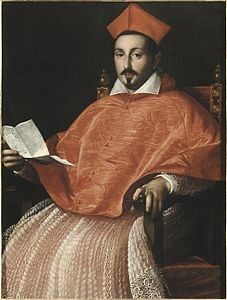

However, there may have been an ulterior motive given the fact that d’Arpino was indeed wrongly accused yet somehow still punished. The paintings sequestered by Pope Poalo V were donated to Scipione Caffarelli-Borghese, becoming part of his own private collection in the Galleria Borghese, where this painting remains today.

Caffarelli-Borghese just happened to be the nephew of the Pope, and an avid art collector, perhaps a coincidence or perhaps a conflict of interests. Was it all a trap? Was it actually a contrived set up for Caffarelli-Borghese to get his hands on some of the best paintings in Italy at the time? The vice of Greed, like that of lust and gluttony, is an excess of desire, in this case for the accumulation of wealth and material riches. It becomes a mortal sin when the object of obtaining wealth leads to theft, violence or trickery. Coincidently, the colour yellow is often associated with greed.

Envy

The fact that the Galleria Borghese was enriched by the addition of d’Arpino’s paintings also alludes to covetousness and envy on the part of Caffarelli-Borghese. Envy is related to pride in the sense that both are concerned with the status of oneself in relation to others. The Catholic Encyclopaedia states, “[Envy] is defined to be a sorrow which one entertains at another’s well-being because of a view that one’s own excellence is in consequence lessened.”. If Caffarelli-Borghese’s own collection benefited from the depriving of another’s, envy could have well been the catalyst.

Sociological relevance…

These events happened, of course, after Caravaggio painted his Young Sick Bacchus, but they are possibly indicative of the environment surrounding Caravaggio at the start of his career. He was obviously talented from the onset, but even his early paintings go beyond simply good technique.

Their ironic tone and allusive iconography, supported by such dramatic realism, appeal to our emotions and at times reveal a dark, cynical side of human nature that is in any case captivating, if only in as much as we see ourselves, and the world around us, reflected in it.

Pride

If the subject’s illness is the defining characteristic of the painting, it is nonetheless unashamed and audacious in its representation. Beyond humility and repentance, Young, Sick Bacchus gazes directly at the viewer, offering himself as an object of art to be admired, revered and sympathised with, through which he retains a certain sense of dignity.

The vice of pride is considered the sin of all sins in as much as it is the belief in one’s own self worth which leads not only to immoral behaviour but a severance from God. The Catholic Encyclopaedia describes pride as “…that state of mind in which a man, through the love of his own worth, aims to withdrawal himself from subjection to Almighty God, and sets at naught the commands of superiors.”.

If we look at the relationship between Caravaggio and d’Arpino at the time through this light, we can see the painting almost as a deliberate act of protest derived from the artist’s own sense of pride and dignity. D’Arpino treated him as a pupil who needed to learn the basics before attempting more elaborate subjects and thus Caravaggio was confined to painting fruit and flowers. Young Sick Bacchus, along side Boy with a Basket of Fruit which was painted in the same period, victoriously demonstrated that Caravaggio was capable of much more, as he was to become one of the most influential Baroque painters and one of the most celebrated artists of all time.

The fact that Bacchus is potrayed as sick, weak and imperfect yet still profoundly beautiful and worthy of our admiration is conceivably a reflection of this sentiment in Caravaggio’s early career as a painter.

The subversion of divine beauty…

In the choice of such a subject, some critics point to an allusion to the contrast between the immaculate Apollo and the flawed Bacchus. Apollo, synonymus with perfection, order and divine beauty is subverted in the representation of Bacchus, symbol of drunkenness, disorder and debauchery, living in the throws of ecstasy and embracing the pleasures of life. What’s more, the divine clothed in a natural, imperfect human condition subverts not only superior authority but also the conventional perception of beauty.

No longer virtuous and splendidly ideal, no longer absolute, Bacchus’s painful smile denotes a beauty that is fragile and transient, shifting between the margins of morality, tainted by desire, deformed by decay, and as complex as the reality of living is.

Nobel rot and the Nectar of the Gods…

Caravaggio’s realism flourishes within this complexity, where even absolute symbols dissolve and coexistent contrasting elements give light to all that exists in between.

This is exquisitely reflected in the bunch of grapes Bacchus is holding. Is it a reference to the passion of Christ as Christian iconography would indicate, is it a symbol referencing the identity of the subject as the God of wine, or is it something more?

Looking closer at the grapes, we can see that two of them show signs of rotting. Why should this rot be none other than Botritys Cinerea, also known as the noble rot, which afflicts grapes yet produces superb, delectably sweet wines? Through this intricate detail, Caravaggio may well be illustrating that there is a certain nobility within decay, if only in its transformation, just as there is glory within imperfection, life within death, and beauty within ugliness.

If there is one wine that embraces the spirit and complexity of this painting in all its vividness and intensity, that wine would certainly be Sauternes. A wine produced from grapes plagued by rot that results in a symphony for the senses, full of rich, complex aromas, and bittersweet flavours. That could not be defined better that “The Nectar of the Gods”.

Sources: Aronson, JK, Ramachandran, M, “The Diagnosis of Art: Caravaggio’s Jaundiced Bacchus”, Di Vito, Mauro, “Iconografia di Caravaggio attraverso gli autoritratti veri e presunti”, www.arteworld.it, www.caravaggio.org, www.deadlysins.com, www.galleriaborghese.beniculturali.it, www.lartte.sns.it/ripa/iconologia, www.newadvent.org